Przemysław Żywiczyński, Marta Sibierska, Sławomir Wacewicz, Joost van de Weijer, Francesco Ferretti, Ines Adornetti, Alessandra Chiera and Valentina Deriu

Pantomime, understood as a form of embodied communication (Żywiczyński et al. 2018), has become one of the most important research topics in the field of language origins (Zlatev et al. 2017, Abramova 2018, Żywiczyński et al. et al. 2021). Pantomimic scenarios of language origins (e.g. Donald 1991, Tomasello 2008, Arbib 2012, Gärdenfors 2017, Ferretti et al. 2017, Zlatev et al. 2020) rest on a number of assumptions, the most important of which concerns its robust iconicity (Zlatev et. Al. 2020; cf. Sonneson’s (2007) notion of primary iconicity) and the resultant claim that it is free from communicative conventions (sensu Lewis 1969), and more specifically semiotic conventions (Zlatev 2014). Although plausible, these two assumptions have not been put to empirical testing.

Here, we present a study that focuses on the postulate of the non-conventionality of pantomime. We assume, however, that the lack of semiotic conventions does not necessarily preclude micro-conventions resulting from environmental (e.g. the level of noise; Kendon 2004, Kita 2009) and cultural differences (e.g. praxic conventions; Żywiczyński et al. 2021; cf. Zlatev’s (2014) notion of “mimetic schemas”). This led us to hypothesise that pantomimes are easier to interpret when both the actor (i.e. the mime) and the matcher (i.e. those guessing their meaning) share the same culture, compared to the actor having a different cultural background from the matcher.

In the study, 32 amateur “actors” (16 Italian, 16 Polish; all students, half were female) were shown 20 cartoon-like drawings of simple transitive events with reversible Agents and Patients (e.g. “Girl – Push – Man”). Each actor enacted each drawing, resulting in 640 videoclips. 60 Polish and 60 Italian university students (half were female) took part in the study as matchers. Each matcher saw 60 randomly selected clips, balanced for Actor’s nationality, and matched each clip to its corresponding drawing in the original matrix of 20 drawings (chance rate = 5%). We operationalised communicative success as the proportion of correct guesses (cf. referential games).

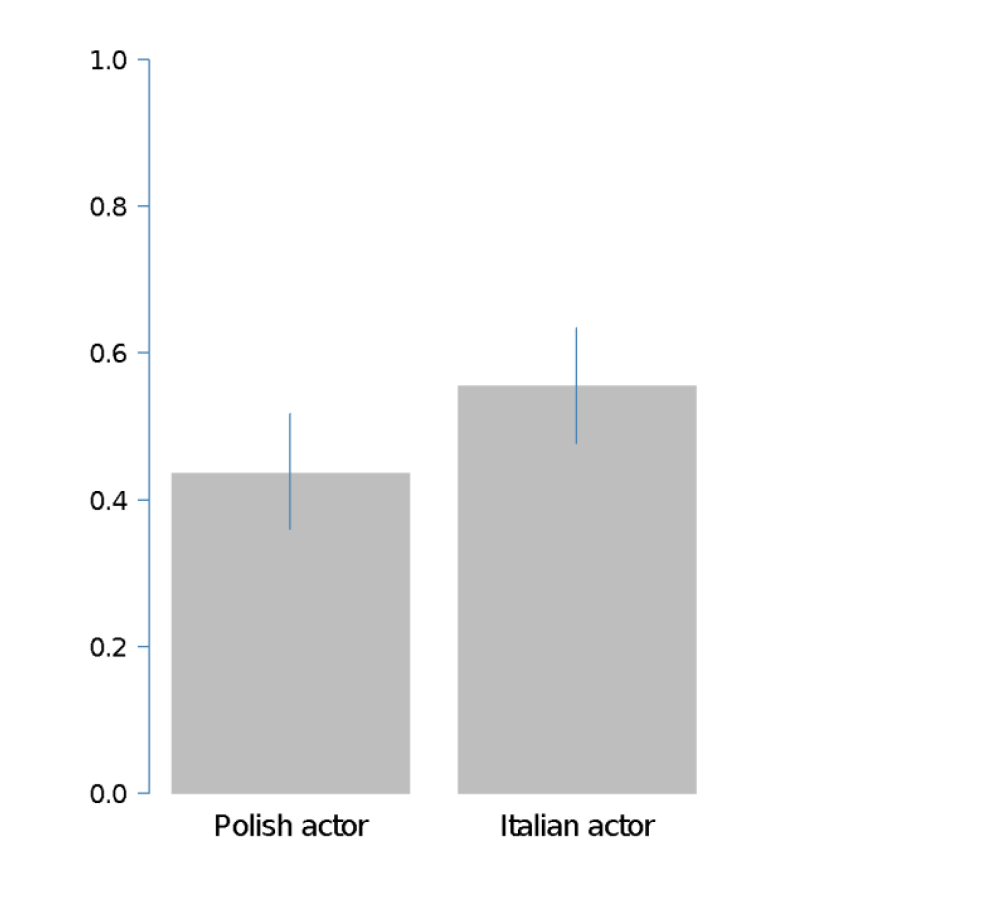

Contrary to our hypothesis, the overall proportion of correct responses was similar in the two groups, with no significant differences when the actors and matchers were from the same vs. from different cultures. Moreover, pantomimes performed by Italian actors were identified correctly considerably more often than those performed by Polish actors. Additionally, this advantage was comparable across the two groups of participants.

Four mixed effects logistic regression models were compared to evaluate the results. These models included:

● no predictors of interest;

● only actor nationality;

● actor nationality and participant nationality as main effects;

● actor nationality and participant nationality including an interaction.

All the four models included random effects for participant and item (video clip). The results of the comparison showed a significant model improvement for the model with actor nationality compared to the model without any predictors of interest (likelihood ratio test: chi-squared = 87.605, df = 1, p = .000), but no significant additional improvements for models including participant nationality. The predicted values with 95% confidence intervals of the chosen model are shown in Figure 1.

We discuss these results in the light of post-hoc analyses focused on the use of particular pantomimic strategies, and especially in the context of the core assumptions of pantomimic scenarios of language origin.

References

Abramova, E. 2018. The role of pantomime in gestural language evolution, its cognitive bases and an alternative. Journal of Language Evolution 3 (1), 26–40.

Arbib, M. 2012. How the Brain Got Language. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Donald, M. 1991. Origins of Modern Mind: Three Stages in the Evolution of Culture and

Cognition. Harvard University Press, New York.

Ferretti, F., Adornetti, I., Chiera, A., Nicchiarelli, S., Magni, R., Valeri, G., Marini, A. 2017.

Mental Time Travel and language evolution: a narrative account of the origins of human

communication. Language Sciences 63, 105–118.

Gärdenfors, P. 2017. Demonstration and pantomime in the evolution of teaching. Frontiers in

Psychology 8, 415, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00415.

Kendon, A. 2004. Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Kita, S. 2009. Cross-cultural variation of speech-accompanying gesture: A review. Language

and Cognitive Processes 24 (2), 145–167, doi: 10.1080/01690960802586188.

Lewis, D. 2002 (1969). Convention. A Philosophical Study. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

Sonesson, G. 2007. From the meaning of embodiment to the embodiment of meaning: a study

in phenomenological semiotics. In: Ziemke, T., Zlatev, J., Frank, R. (eds.) Body, Language,

Mind. Vol 1: Embodiment. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, pp. 85–128.

Tomasello, M. 2008. Origins of Human Communication. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Zlatev, J. 2014. Image Schemas, Mimetic Schemas, and Children’s Gestures. Cognitive

Semiotics 7, 3–30.

Zlatev, J., Wacewicz, S., Żywiczyński, P., van de Weijer, J. 2017. Multimodal-first or

pantomime-first? Communicating events through pantomime with and without vocalization.

Interaction Studies 18 (3), 454–477, doi: 10.1075/is.18.3.08zla.

Zlatev, J., Żywiczyński, P., Wacewicz, S. 2020. Pantomime as the original human-specific

communication system. Journal of Langauge Evolution 5, 156–174, doi: 10.1093/jole/lzaa006.

Żywiczyński, P., Wacewicz, S., Sibierska, M. 2018. Defining pantomime for language

evolution research. Topoi 37, 307–318, doi: 10.1007/s11245-016-9425-9.

Żywiczyński, P., Wacewicz, S., Lister, C. 2021. Pantomimic fossils in modern human

communication. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 20200204, doi:

10.1098/rstb.2020.0204.

References

Abramova, E. 2018. The role of pantomime in gestural language evolution, its cognitive bases and an alternative. Journal of Language Evolution 3 (1), 26–40.

Arbib, M. 2012. How the Brain Got Language. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Donald, M. 1991. Origins of Modern Mind: Three Stages in the Evolution of Culture and

Cognition. Harvard University Press, New York.

Ferretti, F., Adornetti, I., Chiera, A., Nicchiarelli, S., Magni, R., Valeri, G., Marini, A. 2017.

Mental Time Travel and language evolution: a narrative account of the origins of human

communication. Language Sciences 63, 105–118.

Gärdenfors, P. 2017. Demonstration and pantomime in the evolution of teaching. Frontiers in

Psychology 8, 415, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00415.

Kendon, A. 2004. Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Kita, S. 2009. Cross-cultural variation of speech-accompanying gesture: A review. Language

and Cognitive Processes 24 (2), 145–167, doi: 10.1080/01690960802586188.

Lewis, D. 2002 (1969). Convention. A Philosophical Study. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

Sonesson, G. 2007. From the meaning of embodiment to the embodiment of meaning: a study

in phenomenological semiotics. In: Ziemke, T., Zlatev, J., Frank, R. (eds.) Body, Language,

Mind. Vol 1: Embodiment. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, pp. 85–128.

Tomasello, M. 2008. Origins of Human Communication. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Zlatev, J. 2014. Image Schemas, Mimetic Schemas, and Children’s Gestures. Cognitive

Semiotics 7, 3–30.

Zlatev, J., Wacewicz, S., Żywiczyński, P., van de Weijer, J. 2017. Multimodal-first or

pantomime-first? Communicating events through pantomime with and without vocalization.

Interaction Studies 18 (3), 454–477, doi: 10.1075/is.18.3.08zla.

Zlatev, J., Żywiczyński, P., Wacewicz, S. 2020. Pantomime as the original human-specific

communication system. Journal of Langauge Evolution 5, 156–174, doi: 10.1093/jole/lzaa006.

Żywiczyński, P., Wacewicz, S., Sibierska, M. 2018. Defining pantomime for language

evolution research. Topoi 37, 307–318, doi: 10.1007/s11245-016-9425-9.

Żywiczyński, P., Wacewicz, S., Lister, C. 2021. Pantomimic fossils in modern human

communication. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 20200204, doi:

10.1098/rstb.2020.0204.