Shiri Lev-Ari, Ivet Kancheva, Louise Marston, Hannah Morris, Teah Swingler and Madina Zaynudinova

Languages are spoken in different social environments. These environments impose different communicative challenges. For example, larger communities might have less shared knowledge and greater difficulty of converging on a shared system. Recent research shows that languages adapt to their social environment [1], and it has been proposed that languages spoken by more people might evolve to have features that make them easier for learning and communication [1-2]. This study tests this hypothesis by examining whether languages spoken by more people are more sound symbolic.

Sound symbolism has been shown to facilitate language learning and processing [e.g., 3-4]. Therefore, if languages spoken by more people need to be easier to learn and use, they might rely more on sound symbolism. Indeed, recent research on facial expressions shows that more heterogeneous communities, which also face greater communicative challenges, use more exaggerated facial expressions, and these are better understood by non-community members [5].

To test whether languages spoken by more people are more sound symbolic, we selected 20 languages spoken by millions of people, avoiding familiar European languages (Median=81.7m; range: 24.5m-1.1billion) and 20 languages spoken by only hundreds or thousands of people (Median=3,750; range: 200-314,000). We generated recordings of the words ‘big’ and ‘small’ in those languages using text-to-speech synthesizers. We selected the words ‘big’ and ‘small’ as there is an established link between front vowels and small size and back vowels and large size [e.g., 6]. 128 participants (native English speakers: N=95) heard the words in random order and guessed whether they meant ‘big’ or ‘small’. If a word sounded familiar, participants indicated that and did not guess the meaning.

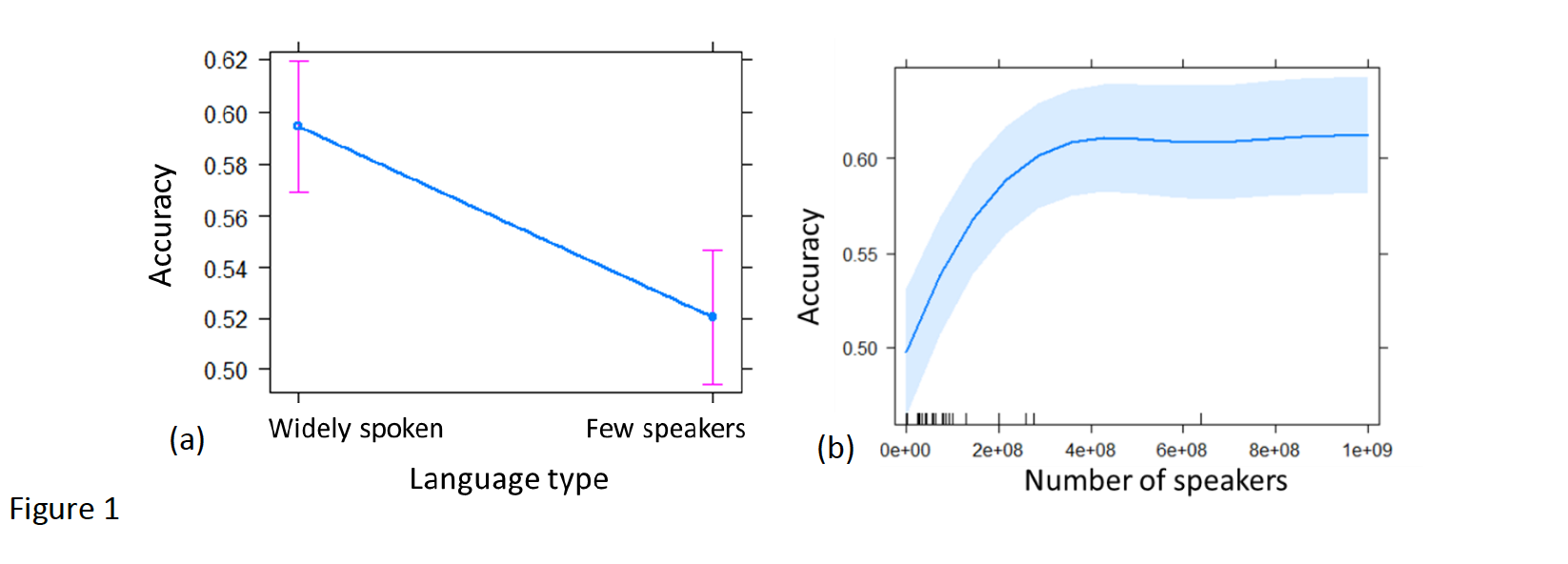

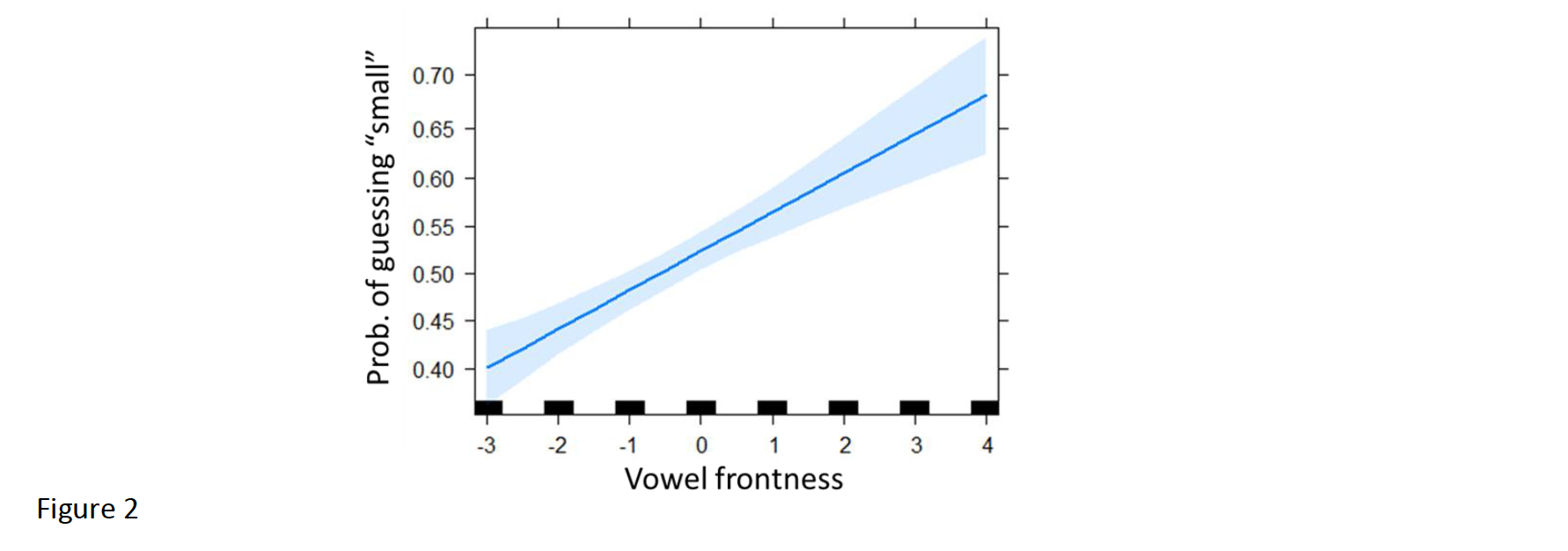

A logistic mixed effects regression revealed that participants were better at guessing word meanings in languages spoken by many vs few people, whether size is coded categorically (β=-0.3, SE=0.15, z=-2, p<0.05; Fig 1a) or using the (log) number of speakers (β=0.03, SE=0.01, z=2.1, p<0.04; Fig 1b). Next, we examined whether participants relied on the established sound symbolic vowel pattern to make their judgments. Indeed, participants were more likely to guess that a word means “big” the more back vs front vowels it had (β=0.16, SE=0.05, z=3.2, p<0.01; Fig 2). Participants exhibited this pattern even though English, which was the instruction language and the native language of the majority of participants, shows the opposite pattern in the words ‘big’ and ‘small’, and these words served as response labels. Participants’ responses then did not merely reflect their native language. Interestingly, widely-spoken languages were not more likely than less common languages to have front/back vowels to indicate small/large size (p>0.1). This indicates that widely-spoken languages rely on different sound symbolic cues. Exploratory analyses suggest that larger languages rely more on sound-symbolic consonants, potentially because there are greater individual differences in vowel production rendering consonant-based patterns more robust in larger communities.

This study shows that widely-spoken languages are more sound symbolic than languages spoken by few people. We propose that this is driven by the need to overcome the greater communicative challenges in larger communities. Some research suggests that languages lose their iconicity with time [e.g., 7 for sign languages]. This study suggests that having a larger community of speakers can lead to maintenance or enhancement of iconicity. Interestingly, the study also suggests that community size might not only influence the degree to which languages rely on sound symbolism but which sound symbolic patterns they exploit.

Refences

[1] Lupyan, G., & Dale, R. (2016). Why are there different languages? The role of adaptation in linguistic diversity. Trends in cognitive sciences, 20, 9, 649-660.

[2] Raviv, L., Meyer, A., & Lev-Ari, S. (2019). Larger communities create more systematic languages. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 286, 1907, 20191262.

[3] Imai, M., Kita, S., Nagumo, M., & Okada, H. (2008). Sound symbolism facilitates early

verb learning. Cognition, 109, 54-65.

[4] Meteyard, L., Stoppard, E., Snudden, D., Cappa, S. F., & Vigliocco, G. (2015). When semantics aids phonology: A processing advantage for iconic word forms in aphasia. Neuropsychologia, 76, 264-275.

[5] Wood, A., Rychlowska, M., & Niedenthal, P. M. (2016). Heterogeneity of long-history

migration predicts emotion recognition accuracy. Emotion, 16, 4, 413.

[6] Peña, M., Mehler, J., & Nespor, M. (2011). The role of audiovisual processing in early

conceptual development. Psychological Science, 22, 1419–1421

[7] Frishberg, N. (1975). Arbitrariness and iconicity: historical change in American Sign Language. Language, 696-719.