von Mandy Bartesch, Ava Braus und Lina Langpap

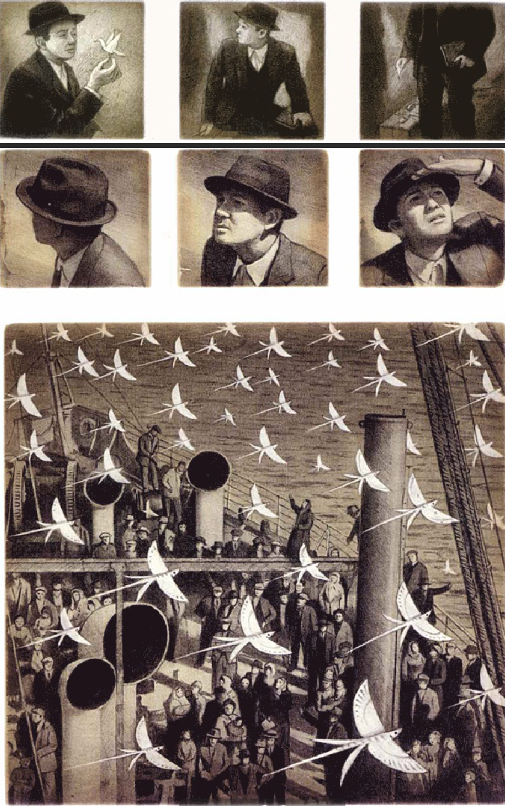

Eine junge Frau steht allein am Ufer einer Art unterirdischen Sees. Giftige Dämpfe wabern durch die Luft, sie kann kaum atmen. Die Oberfläche dessen, was Wasser sein sollte, aber keines ist, kräuselt sich, Tentakel tauchen aus den dunklen Tiefen empor, greifen nach ihr. Der Geruch von Diesel steigt ihr in die Nase.

Kaaron Warrens Kurzgeschichte „Das Dieselbecken“ baut stark auf Elementen des Lovecraftschen Horrors auf, der Furcht vor dem Unbekannten und dem, was wir nicht verstehen, um in den Lesenden ein Gefühl der Beklommenheit und des Schreckens hervorzurufen. Das Grauen steigert sich langsam, aber stetig, bis am Ende schließlich die abscheuliche Kreatur enthüllt wird, die den Kern der Geschichte ausmacht. Als Lesende verfolgen wir den Abstieg der Protagonistin in ein Tunnelsystem unter dem Old Parliament House in Canberra. Das Gebäude sieht nur noch wenige Touristen, seit das Gerücht die Runde macht, es sei asbestverseucht.

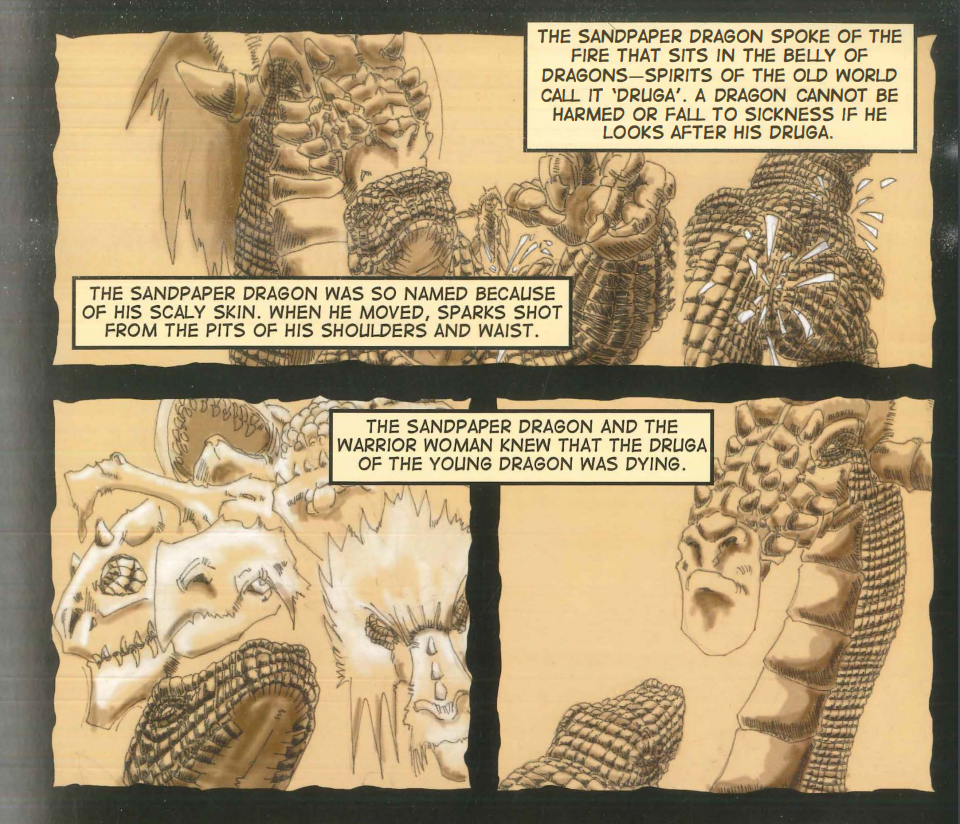

Die quasi-namenlose Protagonistin, die von ihrem verstorbenen Vater den Spitznamen Jenny Haniver bekommen hat, ist Sexarbeiterin, wohnt in ihrem Auto und besitzt die einzigartige Gabe, Geister wahrnehmen und mit ihnen kommunizieren zu können. Einer der Geister erzählt ihr, dass es in den Tunneln und Höhlen unter dem alten Regierungsgebäude Becken voller Diesel gäbe, Überbleibsel aus dem Krieg, aus denen sich Geld machen ließe. In Begleitung eines Mannes namens Lance, der im Old Parliament House arbeitet, folgt sie dieser Spur in die dunklen Tunnel hinab. Es stellt sich heraus, dass es tatsächlich ein Dieselbecken unter dem Gebäude gibt, aber das ist nicht das einzige, was Jenny dort findet. Das Becken wird von einem seltsamen Besucher bewohnt, einem, dem es nach frischer Luft giert, der jedoch nicht imstande ist, die dunkle Grotte zu verlassen, die über die Jahre zu seinem Gefängnis geworden ist …

Wie Lovecraft baut auch Warren die düstere Atmosphäre ihrer Geschichte nur langsam auf und steigert den Schrecken mit jedem Schritt, den Jenny tiefer in die Tunnel hinab steigt. Erst ganz am Ende enthüllt sie das ganze Ausmaß des Grauens, das dort unten lauert. Es ist eine existentielle Art des Horrors, die sich nicht auf blutiges Gemetzel oder billige Schockeffekte verlassen muss, um unheimlich zu sein. Diese dichte, spannungsgeladene Atmosphäre ins Deutsche zu übertragen, erwies sich als recht schwierig, denn sowohl als Lesende als auch als Übersetzende erleben wir die Ereignisse ausschließlich durch die Augen der Protagonistin: Wenn sie verwirrt ist, sind wir es ebenso, wenn sie Schwierigkeiten hat, zu unterscheiden, was echt ist und was nicht, geht es uns ebenso. Die Art, wie sie ihre Erlebnisse schildert, ist besonders oft durch Ellipsen geprägt, etwa wenn sie die Erinnerungen an ihren Vater völlig abrupt, sogar ohne Satzzeichen abbricht (Warren 74). Als Übersetzende müssen wir uns fragen, ob wir diese Leerstellen füllen oder doch lieber leer lassen sollen, und ob das etwas daran ändern würde, wie ein deutschsprachiges Lesepublikum die Geschichte wahrnähme.

Darüber hinaus stellt sich die Frage, ob wir während des Übersetzungsprozesses Erklärungen für Kulturspezifika einfügen sollten oder nicht. So finden sich im Ausgangstext Textelemente wie Old Parliament House, tent-embassy, oder Summernats, die in der Kultur von Australien, speziell von Canberra eingebettet sind und bei denen wir als Übersetzer erwägen müssen, inwieweit wir als Kulturmittler agieren sollen. Etwa der Begriff Summernats, ein in Canberra jährlich stattfindendes Autofestival, bedarf in der Übersetzung eine zusätzlichen Erklärung. Ein weiteres Beispiel: gibt man beispielsweise den Begriff tent-embassy bei Google ein, so lässt sich leicht feststellen, dass es hierfür eine feststehende deutsche Übersetzung gibt, und zwar Zelt-Botschaft. Jedoch gehört dieser Begriff und der damit zusammenhängende kulturelle Kontext nicht zum Allgemeinwissen deutscher LeserInnen. Daher haben wir uns dazu entschlossen, eine Fußnote einzufügen.

Weitere Übersetzungsprobleme, auf die wir gestoßen sind, waren die Nachbildung der eigenen Stimmen der Figuren und die mit dem Genre des Kosmischen Horrors zusammenhängende Schwierigkeit der Erschaffung einer spannungsgeladenen Atmosphäre und eines Gefühls des Unbehagens, das bei H.P. Lovecraft mit der Furcht vor dem Unbekannten verbunden ist. Warren‘s Kurzgeschichte baut dieses Unbehagen langsam auf, enthält mehrere Plot-Twists und endet mit einer schrecklichen Enthüllung, die in der Übersetzung genauso schockierend sein musste, damit der Horror-Aspekt der Geschichte funktioniert. Während die Sprache bei Lovecraft mit seinen langen Schachtelsätzen etwas altmodisch und fast schon gestelzt wirkt, spricht die Protagonistin Jenny in „Das Dieselbecken“eher einfach, direkt und umgangssprachlich. Doch auch hier finden sich einige Bilder, die schon ins Absurde gehen, etwa wenn Jenny den Geruch der unterirdischen Grotte mit dem eines im Dunkeln vor sich hintrocknenden Spüllappens vergleicht (Warren 75). Dann ist da noch Lance, der in sehr ominösem Ton spricht, aber auch manchmal absurde Lächerlichkeiten von sich gibt. Diese Eigenheiten der Figuren sollten auch in der Übersetzung nicht verloren gehen.

Wir hoffen, diese Besonderheiten von Genre, Figuren und unserer Übersetzung gerecht geworden zu sein und wünschen allen LeserInnen viel Spaß mit der Geschichte! Ihr findet sie hier.

A young woman standing alone on the shore of what seems to be an underground lake. Toxic fumes waft through the air, she can barely breathe. The surface of what should be water but isn’t ripples; tentacles emerge from the murky depths, reaching out for her. The smell of diesel fills her nose.

Kaaron Warren’s short story “The Diesel Pool” heavily draws on elements of Lovecraftian horror, on the fear of that which is unknown, that which we do not understand, in order to invoke uneasiness and dread in the reader, building up to the grand reveal of the abominable creature at the heart of the story. As readers, we follow the protagonist’s journey into the underground beneath Canberra’s Old Parliament House, a building mostly abandoned by tourists since the rumor of asbestos in the walls made its rounds.

The kind-of-nameless protagonist, nicknamed Jenny Haniver by her late father, is a sex worker operating from her car, who possesses the unique ability to see and communicate with ghosts. One of the ghosts leads her to believe that in the tunnels and caverns beneath the old government building, there are pools of diesel, remnants of the war from which she could potentially make money. She follows this lead into the dark tunnels, accompanied by Lance, a man working at Old Parliament House. As it turns out, there is a diesel pool beneath the building, but that is not the only thing Jenny finds there. The pool is occupied by a strange visitor, one that is hungry for fresh air but unable to leave the dark cavern that has become his prison over the years …

Like Lovecraft, Warren builds her atmosphere of terror slowly, raising the level of dread with every step Jenny takes further down the tunnels, only revealing the full scale of horrors lurking down there at the very end of the story. It’s an existential kind of horror that does not need to rely on gore or cheap thrills to be scary. Translating this dense atmosphere of suspense into German proved to be difficult, since we, as readers and translators, experience the story exclusively through the eyes of the protagonist – when she is confused, so are we, when she has difficulty discerning what is real or not, then so do we. The way she narrates her experience for us is especially often characterized by ellipses, for example when her memories of her father get interrupted abruptly (Warren 74). As translators we have to ask ourselves whether to fill those blank spots or leave them blank and whether that would change how German readers would then perceive the story.

There is also the question as to whether we should include explanations for culturally specific elements of the story. The story contains concepts specific to Australian, specifically Canberran, culture. As translators, we had to decide how much of it to explain to readers. There is, for example, Summernats, the name of an annual car festival held in Canberra, that needs explanation. Another example: If you search up the term tent-embassy on Google, you easily find the German term for it: Zelt-Botschaft. But it is not that simple, since most German readers won‘t be familiar with the cultural and political context of the term — the tent-embassy means a tent erected by Indigenous Australians to symbolize their protest against injustice and violence perpetrated against them by the European settlers. So we decided to add an explanatory footnote. Attention should also be paid to finding respectful, appropriate terms when mentioning Indigenous people in the translation.

Another translation difficulty was recreating the the characters‘ voices and the sense of dread and tense atmosphere of the Cosmic Horror genre, which is connected to the fear of the strange and unknown in Lovecraft‘s writing. Warren‘s story slowly builds up the dread, contains several plot twists, and ends with a horrific revelation that needed to be just as hard-hitting in German as in the original to make the translation work. While Lovecraft‘s syntax is old-fashioned and sometimes stilted, the voice of Warren‘s narrator is direct and colloquial. Still, some of her descriptions seem almost absurd, like her comparison of the monster‘s smell to an „an old dishrag left to dry in the dark“ (Warren, 75). Then there is Lance, whose tone is ominous, coupled with occasional absurdities. We tried to not let these aspects of the characters to get lost in the translation

All in all, we hope to have done justice to these specifics of genre, characters and Australian culture in our translation and wish all readers of „Das Dieselbecken“ a great time with the story! Here it is!