Experience Using ANNIS

After getting used to the surface, I found ANNIS to be very user-friendly. The Query-Builder allows for a combination of all kinds of prompts. In theory, this could be used to find out how many non-English words in our corpus are proper nouns, nouns, adjectives, etc. Such information would be useful to find evidence for patterns found in post- and/or multilingual novels, or might even lead to the discovery of patterns so far missed.

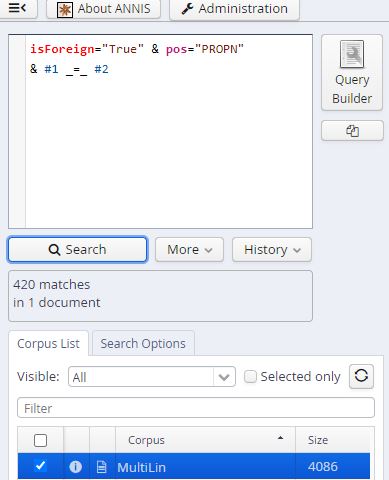

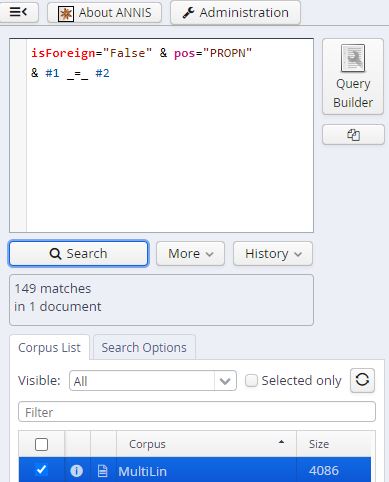

However, the faulty machine annotation, which inevitably became part of our corpus, made work with the findings rather difficult. Firstly, most non-English words were simply classified as proper nouns. ANNIS underlines the absurdity of that number: If one looks for words which are both non-English and proper nouns, one receives over 400 matches. If one looks for words which are English and proper nouns, the number is far smaller.

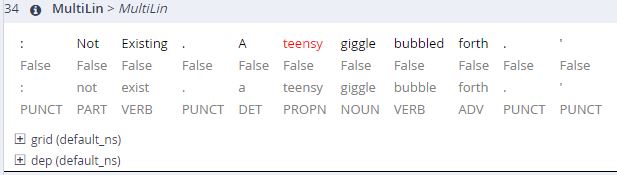

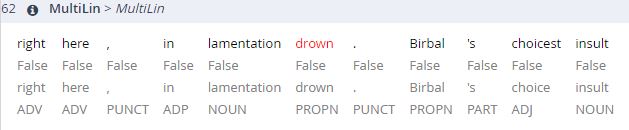

The results above are already fishy. Something cannot be right here. Spoiler alert: We all know it is the preceding machine annotation. Playing around with ANNIS some more, I also found instances where the machine had been unable to annotate English words correctly, resulting in falsified ANNIS search results.

Given that ANNIS can work with several languages at once, I would really like to see a manually annotated corpus of post- and/or multilingual literatures. This experience strengthened my appreciation for corpora, but brought forward a lack of trust in machine annotation. I had expected at least the annotation of English words to be correct.

Our Little Experiment With (AI) Translation

We conducted a little experiment, translating our sentences ourselves and also having them translated by AI. Interestingly, the AI, such as DeepL and Google Translate, displayed tendencies similar to those of the machine annotation. Non-English words were combined with other nouns into compounds. For instance, „fallahi accent“ (meaning: rural accent, the accent used by farmers) became „Fallahi-Akzent“. In other words, both machine annotation and AI translation tools have a tendency to deal with non-English words by interpreting them as nouns or proper nouns, rather than what they actually are.

Dear Anna, you're right, the query-builder is really useful for more specific searches and will be an efficient tool to find patterns. I made the same observation with the amount of 'proper nouns', but I didn't take a closer look at English proper nouns. It's baffling that some English words got annotated incorrectly as proper nouns. I wonder what caused that. I agree that a manually annotated multilingual corpus would be interesting to see. Of course that would require a better understanding of the languages we're dealing with, so the annotations are as accurate as possible. I have also looked into AI translations for my sentences, though I made a different observation. I only compared Google Translate and ChatGPT, and ChatGPT yielded slightly better/accurate translations of the sentences. One sentence had a lot of specific food items, ChatGPT kept those untranslated while Google translated them to a close German equivalent, but even then it wasn't very accurate. For example, it translated 'bagoong' - a type of fermented fish paste - into 'Sardellen', which clearly is not the same thing. Anyway, we can't fully rely on AI translations yet and maybe that's a good thing ʕ ᵔᴥᵔ ʔ