Introduction

In the winter term of 2022/23, I participated in the ‘Demarginalising Orature’ seminar, organised and held by Dr. Eva Ulrike Pirker, Tasun Tidorchibe and Jana Mankau. The seminar aims at “decolonizing knowledge and making knowledge (and primary materials) from a Global South context available in a responsible way” [1]. We, the participants, were “introduced to Ghana’s literary culture and multiethnic society; the problem of major and minor languages and forms of expression; orality, literacy and digital media cultures; power relations in the postcolony and [our] bearing on acts of cultural translation” [1]. In an attempt to help demarginalise orature, we worked on digitising a collection of Konkomba folktales by encoding them with TEI so they can later be transformed into HTML format and uploaded to the Centre for Translation Studies’ github. We also subtitled a number of folktale narrations so the respective videos could be published in the HHU Mediathek and be made available to a broader audience. These documents can also be used for research purposes. Thus, we are contributing to the preservation and demarginalisation of Konkomba oral traditions.

Orature and Orality

As mentioned above, the seminar aims at demarginalising orature; oral literature. According to Turin et al., orature “broadly includes ritual texts, curative chants, epic poems, folk tales, creation stories, songs, myths, spells, legends, proverbs, riddles, tongue-twisters, recitations and historical narratives” [2]. Orality, in contrast to literacy, is characterised by its “immediacy, ephemerality, unpredictability, flexibility” [3], it is communication by spoken word and it is dependent on the teller’s memory and “occasion-bound” [3]. Furthermore, it is quite difficult to assign any authorship to oral traditions, as, according to Bisilki, they are usually passed on from the older generations to the next [4] and regarded “as communal intellectual property” [2] by the respective communities.

In the past, orality has often been regarded as inferior to literacy. The roots of this assumption lie, amongst other things, in colonialism. Bandia writes that “[m]odernity has ascribed a stigma to the concept of orality which has become synonymous with ‘backward’ and ‘primitive’” [5]. Thiong’o points out that “[t]he hegemony of the written over the oral comes with the printing press, the dominance of capitalism, and colonization. This hegemony, or its perception, has roots in the rider-and-the-horse pairing of master and slave, or colonizer and colonized, a process in which the latter begins to be demonized as the possessor of deficiencies, including of languages” [6].

But oral traditions have a long and rich history and are an integral part of many communities’ cultures all over the world. As Turin et al. point out, “oral literature such as narrative and song often serve as important cultural resources that retain and reinforce cultural values and group identity” [2]. This is the case for Konkomba folktales as well. Folktales (called itiin in Likpakpaln, the language of the Konkomba people) can have various purposes, depending on the context in which they are told, by or to whom they are told, what the folktale is about etc. They often contain moral lessons or offer explanations for why things are the way they are. But what applies to all folktales is that they are “sources of indigenous knowledge” [7].

To give an example, one of the folktales discussed in the seminar is called “Why he Wasp has a tiny Waist”. This particular folktale was told by Waja Ngalbu in Chamba, Ghana. To quote the introduction of the folktale: “The following story relates how the wasp’s self-exile from his community eventually deformed him. It presents the wasp as a loner who refuses to participate in communal activities and thus incurs the wrath of his kith and kin. The story, grounded in the communal spirit of Konkomba funerals (particularly the kinachuŋ cultural dance), celebrates teamwork and depicts the centrality of communal living among Konkombas. The storyteller makes this clear at the outset of his narrative when he commences his tale with its moral lesson before relating the tale itself” [8]. So the folktale features an animal character (the Wasp, called ulangben in Likpakpaln) that interacts with human characters, as many Konkomba folktales do. According to Thiong’o, “in the narratives of orature, humans, birds, animals, and plants interact freely, often change into each others’ forms, and share language” [6]. The folktale gives an explanation to a real phenomenon (wasps have tiny waists) and it contains a moral lesson: the folktale highlights the importance of a communal spirit within the community. In Konkomba culture, it is important to attend communal activities like funerals or participate in farm work or other activities such as shelling maize. A folktale therefore transports values and elements of the respective culture, which, again, highlights the fact that oral traditions are an important source of indigenous knowledge and “essential vehicles for transmitting language and culture” [7].

The Konkomba People and Language

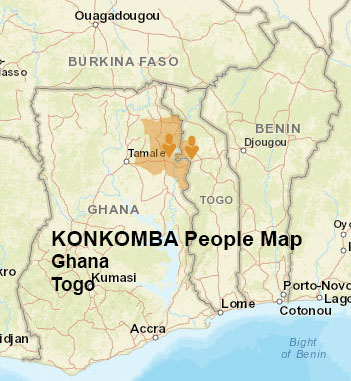

I have already touched on some aspects of Konkomba life, values and traditions, now I would like to give some more background information. The Konkomba people live in the area of the “Oti valley in the northern section of the Ghana-Togo border” [9] (see map below). It is estimated that there are a little over 1,2 million Konkomba people in total, about 112,000 of whom are living in the Togo area [7]. According to Kachim, it is widely agreed upon that the Konkomba are “one of the aboriginal groups of northern Ghana” [9].

When discussing Konkomba history, it is important to mention the aspect of colonisation. The Konkomba people were affected by this through imperialist Germany’s rule between 1884 and 1914. This is when they occupied Togo (and also Cameroon, Tanzania and Namibia). Eventually, “the German colonial empire was taken over by the French and the British” [10]. But the German rulers were met with resistance, also by Konkombas, for example “[o]n 14 May 1895, a German troop stationed at Katchamba, and led by the German von Carnap-Quernheimb, was violently attacked by Konkomba warriors armed with poisoned arrows” [11].

The Konkomba society is patrilineal, so the male offspring will inherit, a Konkomba community is also structured politically – there are “chiefs, elders, clan heads, family heads” [7] and the Konkomba believe in “God, lesser gods, ancestors, satan, evil spirits, reincarnation, etc.” [7]. Their primary occupations are farming and trading, which is why sometimes, during folktale telling sessions, farming related activities are done simultaneously (like shelling maize etc., an example of this can be seen and heard in this video).

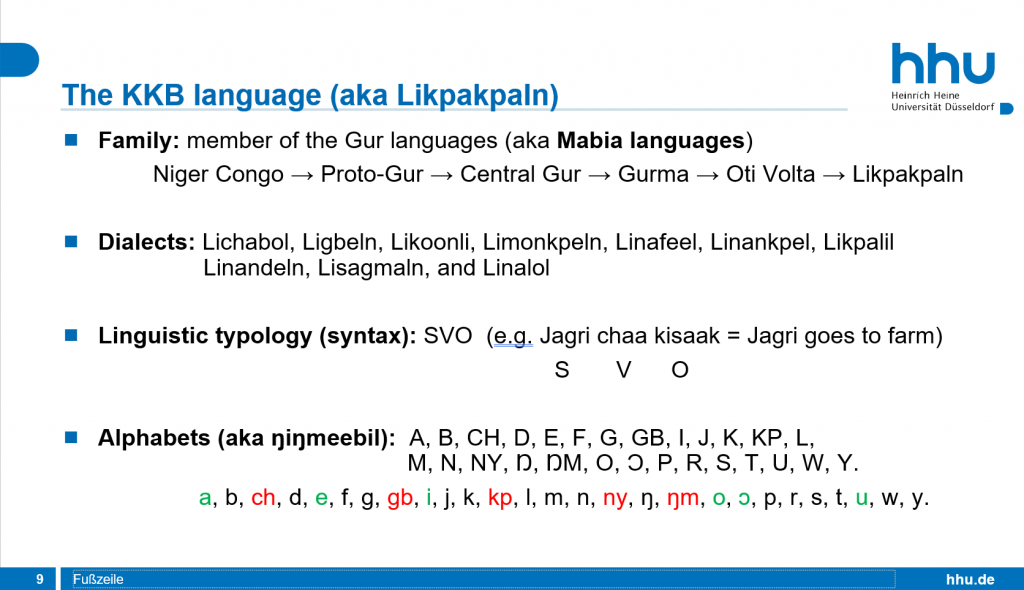

Further information regarding Likpakpaln can be extracted from the image below:

Final remarks

Participating in the “Demarginalising Orature” seminar was a very enriching experience. Not only did I gain skills in the fields of coding and video editing, I was also able to broaden my horizon by learning about the Konkomba society and language. As folktales are a source of indigenous knowledge, it is very important to preserve them. But this has to happen in a responsible and sensitive way (keeping in mind the colonial history and marginalisation). We have to remember that this is not our knowledge, so we have to give visibility to the original owners / holders of the knowledge (this is why, for example, the narrators of the folktales are always mentioned in the XML / PDF files and videos). Visibility is very important in the field of translation as well. That is why a foreignising mode of translation was used by Tasun Tidorchibe to translate the folktales from Likpakpaln into English. Here, you can see how some words in the text are untranslated. They are also listed at the bottom of the file in a glossary which gives explanations to the Likpakpaln terms. In this way, the source culture and language are not entirely “covered up”, but they are still visible to the reader.

I can wholeheartedly recommend this seminar to any of my fellow students interested in doing something useful and meaningful.

Sources:

[1] Demarginalising orature – Translating minor forms into the digital age. (n.d.). https://lsf.hhu.de/qisserver/rds?state=verpublish&status=init&vmfile=no&publishid=234298&moduleCall=webInfo&publishConfFile=webInfo&publishSubDir=veranstaltung

[2] Turin, M., Wheeler, C., & Wilkinson, E. (2013). Oral Literature in the Digital Age: Archiving Orality and Connecting with Communities. Open Book Publishers, xiiii, xix, xix-xx. https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0032

[3] Tidorchibe, T. (n.d.). Introduction to orality and literacy, 12. https://uni-duesseldorf.sciebo.de/apps/onlyoffice/600532749?filePath=%2FDemarginalising%20Orature%20-%20Course%20-%20Winter%202022%2FPresentations%2FDemarginalising%20orature_introductory%20session2.pptx

[4] Bisilki, K. A. (n.d.): Folktales And Gender Among The Bikpakpaam ‘Konkomba’ Of Ghana, 349.

[5] Bandia, P. (2018). Orality and Translation. Routledge, 108-109.

[6] Thiong’o, N. w. (2012). The Oral Narrative and the Writing Master. Orature, Orality, and Cyborality. In Globalectics: Theory and the Politics of Knowing. Columbia University Press, 64, 76.

[7] Tidorchibe, T. (n.d.). Folktales as expressive tools for language and culture: the Konkomba context, 7, 12. https://uni-duesseldorf.sciebo.de/apps/onlyoffice/602811744?filePath=%2FDemarginalising%20Orature%20-%20Course%20-%20Winter%202022%2FPresentations%2FFolktales%20as%20expressive%20tools%20for%20language%20and%20culture_by%20Tasun%20Tidorchibe.pptx

[8] Ngalbu, W. / Centre for Translation Studies. (2020). Why The Wasp Has A Tiny Waist, 1. https://github.com/CentreforTranslationStudies/KONKOMBA/blob/main/Why%20the%20Wasp%20has%20a%20tiny%20waist%20Juli%202022.pdf

[9] Kachim, J. U. (2019). View of Origin, migration and settlement history of the Konkomba of Northern Ghana, ca. 1400-1800, 133. https://journal.ucc.edu.gh/index.php/ajacc/article/view/850/428 p. 133

[10] Blackshire-Belay, C. A. (1992). German Imperialism in Africa The Distorted Images of Cameroon, Namibia, Tanzania, and Togo. Journal of Black Studies, 23(2), 236. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/002193479202300207?casa_token=RNGLUXDq7awAAAAA:Z32APCcmpqVVQzBgWW82t0gqUQPQaNhPS849YfPoJSi5X-QON_rlcetEAkNQOnswybPaJoNdZwKbPA

[11] Müller, B. (2022). The ›Mystery‹ of the Konkomba’s Severed Thumbs: Historical Fact, Colonial Rumour or Legend of the Defeated?. Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften Dezember 2021, 15(2), 96. doi:10.14361/zfk-2021-150208

Figure 1: Tidorchibe, T. (n.d.). Introduction to orality and literacy. https://uni-duesseldorf.sciebo.de/apps/onlyoffice/600532749?filePath=%2FDemarginalising%20Orature%20-%20Course%20-%20Winter%202022%2FPresentations%2FDemarginalising%20orature_introductory%20session2.pptx

Figure 2: Tidorchibe, T. (n.d.). Introduction to orality and literacy. https://uni-duesseldorf.sciebo.de/apps/onlyoffice/600532749?filePath=%2FDemarginalising%20Orature%20-%20Course%20-%20Winter%202022%2FPresentations%2FDemarginalising%20orature_introductory%20session2.pptx

Figure 3: https://www.101lasttribes.com/tribes/konkomba.html

Figure 4: Tidorchibe, T. (n.d.). Folktales as expressive mediums for language and culture: the Konkomba context. https://uni-duesseldorf.sciebo.de/apps/onlyoffice/602811744?filePath=%2FDemarginalising%20Orature%20-%20Course%20-%20Winter%202022%2FPresentations%2FFolktales%20as%20expressive%20tools%20for%20language%20and%20culture_by%20Tasun%20Tidorchibe.pptx